By Professor Emeritus Tom Bassett

On July 26, 2018, Chancellor Robert Jones of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign made Native land history a campus-wide topic. His office issued a Land Acknowledgement Statement, which formally recognizes Native Americans as the historical custodians of the land on which the campus is located.

The Chancellor’s Land Acknowledgement Statement states:

As a land-grant institution, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign has a responsibility to acknowledge the historical context in which it exists. In order to remind ourselves and our community, we will begin this event with the following statement. We are currently on the lands of the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Peankashaw, Wea, Miami, Mascoutin, Odawa, Sauk, Mesquaki, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Chickasaw Nations. It is necessary for us to acknowledge these Native Nations and for us to work with them as we move forward as an institution. Over the next 150 years, we will be a vibrant community inclusive of all our differences, with Native peoples at the core of our efforts.

Native American House issued an alternative statement that emphasizes the history of dispossession and the significance of these lands to Native American identity today. It reads:

I/We would like to begin today by recognizing and acknowledging that we are on the lands of the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Piankashaw, Wea, Miami, Mascoutin, Odawa, Sauk, Mesquaki, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Chickasaw Nations. These lands were the traditional territory of these Native Nations prior to their forced removal; these lands continue to carry the stories of these Nations and their struggles for survival and identity.

As a land-grant institution, the University of Illinois has a particular responsibility to acknowledge the peoples of these lands, as well as the histories of dispossession that have allowed for the growth of this institution for the past 150 years. We are also obligated to reflect on and actively address these histories and the role that this university has played in shaping them. This acknowledgement and the centering of Native peoples is a start as we move forward for the next 150 years.

The Chancellor recommended that one of these statements be read at the opening of official university events like Graduation and the Annual Freshman Convocation, as well as at other campus meetings such as symposia, discussion panels, workshops, and receptions. The Land Acknowledgement Statement is the outcome of decades of activism by Native peoples and their allies, much of it focused on eliminating stereotyped American Indian-themed imagery on the Urbana-Champaign campus but also on building an American Indian Studies Program. The statement came after a long overdue “critical conversation” on Native imagery organized by the Office of the Chancellor aimed at healing divisions across campus and the state over the history and 2007 retirement of “Chief Illiniwek,” a stereotyped Indian-themed mascot who used to perform at University of Illinois athletic events.

The Land Acknowledgement Statement refers to more than a dozen Native groups who in the late 18th and early 19th centuries controlled the land that eventually became the state of Illinois. Indeed, when Illinois became the 21st state on December 3, 1818, Indian Nations still legally owned a large part of this territory.

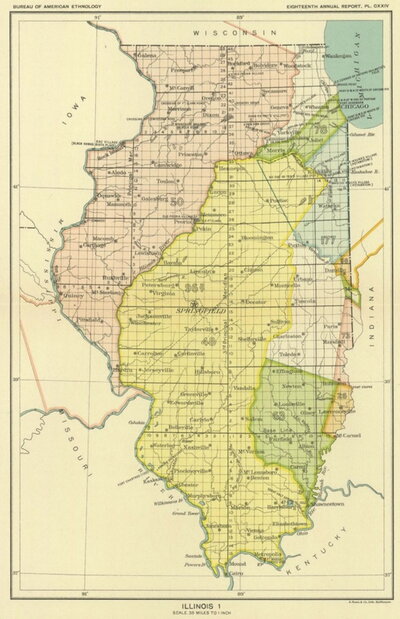

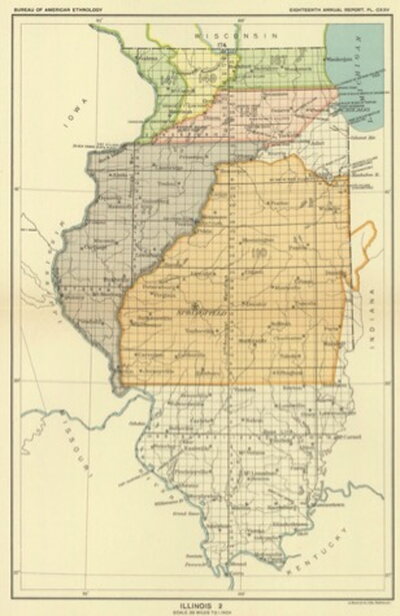

Some background information on Native land transfers helps to put the Land Acknowledgement Statement into an historical geographical context. The short of it is that the state of Illinois is comprised of land ceded to the United States government by Native Nations in more than two dozen treaties that span the period 1795 to 1833. The maps below show the approximate boundaries of these land cessions. The numbers in the accompanying tables correspond to the numbers on each map. The tables also indicate the Nations who participated in the treaty, the date and location of the signing, and the page numbers in Charles Royce’s Indian Land Cessions in the United States in which the treaties are discussed in some detail.

A close reading of these treaties and the circumstances in which they were negotiated reveals considerable deception, inequity, and violence. The earliest treaties were negotiated by William Henry Harrison, Governor of Indiana Territory, who followed a divide-and-rule strategy to obtain Indian land. Harrison’s method was to find someone who could claim land ownership and strike a deal with that person without consulting with other, more legitimate land authorities.

For example, the 1803 Treaty with the Kaskaskia (No. 48 in Figure 1) omitted the rights of the Peoria, Michigamia, Cahokia, and Tamaroa to these lands. A new treaty negotiated in 1818 (No. 96a in Figure 1) recognized these groups’ rightful claims. The Kickapoo rejected both treaties for ignoring its legitimate rights to much of central Illinois. The United States government was forced to negotiate a new treaty in 1819 that recognized the Kickapoo’s land rights (No. 110 in Figure 2). In compensation for ceding fourteen million acres of land, the Kickapoo received a small tract of land in southwestern Missouri and an annuity of $2000 to be paid for fifteen years—a paltry payment for what was to become some of the world’s richest farmland.

The dispossession of Native peoples of Illinois culminated in their forced removal to the west of the Mississippi River in 1830 by President Andrew Jackson. The refusal of many Sauk families to leave their lands in the Rock River area led to the Black Hawk War of 1832. Black Hawk’s autobiography is an eloquent recounting of his people’s experience with discrimination, divide-and-rule politics, violence, and dispossession.

At this year’s celebration of Indigenous People’s Day, a Native student leader read the Land Acknowledgement Statement. For his part, Chancellor Jones expressed the university’s commitment to putting Native history and culture "at the core of our educational efforts." Reading the Land Acknowledgement Statement at the opening of their symposia, receptions, and other meetings, is a simple and effective way for faculty and students to contribute to this educational mission.

Click image to view as large PDF

| Table 1: Treaties related to Native land cessions in Illinois shown in Plate 17 in Indian Land Cessions in the United States. |

| No. 26 & No. 27— Treaty with the Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomi, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Kaskaskia, August 3, 1795 at Greenville, Ohio (Royce 656-57) |

| No. 47—Treaty with the Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Kaskaskia, June 7, 1803 at Fort Wayne on the Miami of the Lake (Royce 664-65) |

| No. 48—Treaty with the Kaskaskia, August 13, 1803 at Vincennes, Indiana (Royce 664-65); and Treaty with the Piankashaw, August 27, 1804 at Vincennes, Indiana (Royce 666-67); Treaty with the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Mitchigamia, Cahokia, and Tamaroa, September 25, 1818 at Edwardsville, Illinois (Royce 692-93) |

| No. 50—Treaty with the Sauk and Fox, November 3, 1804 at St. Louis, District of Louisiana, (Royce 666-67); and Treaty with the Sauk, September 13, 1815 at Portage des Sioux (Royce 680-81); Treaty with the Fox, September 14, 1815 at Portage des Sioux (Royce 680-81); Treaty with the Sauk, May 13, 1816 at St. Louis, Missouri Territory (Royce 680-81) |

| No. 63—Treaty with the Piankashaw, December 30, 1805 at Vincennes, Indiana Territory (Royce 672-73) |

| No. 73—Treaty with the Delaware, Potawatomi, Miami, and Eel River Miami, September 30, 1809 at Fort Wayne, Indiana (Royce 678-79); and Treaty with the Kickapoo, December 9, 1809 at Vincennes, Indiana Territory (Royce 678-79); Treaty with the Wea and Kickapoo, June 4, 1816 at Fort Harrison, Indiana Territory (Royce 680-81) |

| No. 74—Treaty with the Wea and Kickapoo, June 4, 1816 at Fort Harrison (Royce 680-81); and Treaty with the Wea, October 2, 1818, at St. Mary’s, Ohio (Royce 692-93) |

| No. 78—Treaty with the Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomi, August 24, 1816 at St. Louis, Missouri Territory (Royce 680-83) |

| No. 96a—Treaty with the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Mitchigamia, Cahokia, and Tamaroa, September 25, 1818 at Edwardsville, Illinois (Royce 692-93) |

| No. 98—Treaty with the Potawatomi, October 2, 1818 at St. Mary’s, Ohio (Royce 692-93) |

| No. 177—Treaty with the Potawatomi (Prairie and Kankakee Bands) October 20, 1832 at Camp Tippercanoe, Indiana (Royce 738-39) |

Click image to view as large PDF

| Table 2: Treaties related to Native land cessions in Illinois shown in Plate 18 in Indian Land Cessions in the United States. |

| No. 77—Treaty with the Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomi, August 24, 1816 at St. Louis, Missouri Territory (Royce 680-83) |

| No. 110—Treaty with the Kickapoo, July 30, 1819 at Edwardsville, Illinois (Royce 696-97); and Treaty with the Kickapoo (Vermillion Band), August 30, 1819 at Fort Harrison, Indiana (Royce 698-99) |

| No. 147 & No. 148—Treaty with the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi, July 29, 1829 at Prairie du Chien, Michigan Territory (Royce 722-23) |

| No. 149—Treaty with the Winnebago, August 1, 1829 at Prairie du Chien, Michigan Territory (Royce 724-25) |

| No. 174—Treaty with the Winnebago, September 15, 1832 at Fort Armstrong, Rock Island, Illinois (Royce 736-37) |

| No. 187—Treaty with the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi, September 26, 1833 at Chicago, Illinois (Royce 750-51) |

For more information on the Indian land cessions in Illinois see:

(1) Black Hawk (2008) Life of Mà-ka-tai-me-she-kià-kiàk, or Black Hawk. Introduction and notes by J. Gerald Kennedy. New York: Penguin Books.

(2) Grant Foreman (1940) “Illinois and Her Indians,” Papers in Illinois History and Transactions for the Year 1939, pp. 66-111. Springfield: The Illinois State Historical Society.

(3) Charles Royce (1899) Indian Land Cessions in the United States in J. W. Powell (Ed.) Eighteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1896-97. Part two, pp. 521-997. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

For information on the history of stereotyped Indian-themed mascots at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, see:

(1) Jay Rosenstein (1997) In Whose Honor? Documentary film

(2) Carol Spindel (2000) Dancing at Halftime: Sports and the Controversy over American Indian Mascots. New York: New York University Press.

(3) Office of the Chancellor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Chancellor’s Critical Conversation on Native Imagery Report, September 2018.