In Fall 2016, Assistant Professor Brian Jordan Jefferson will offer a new Geography & GIScience course:

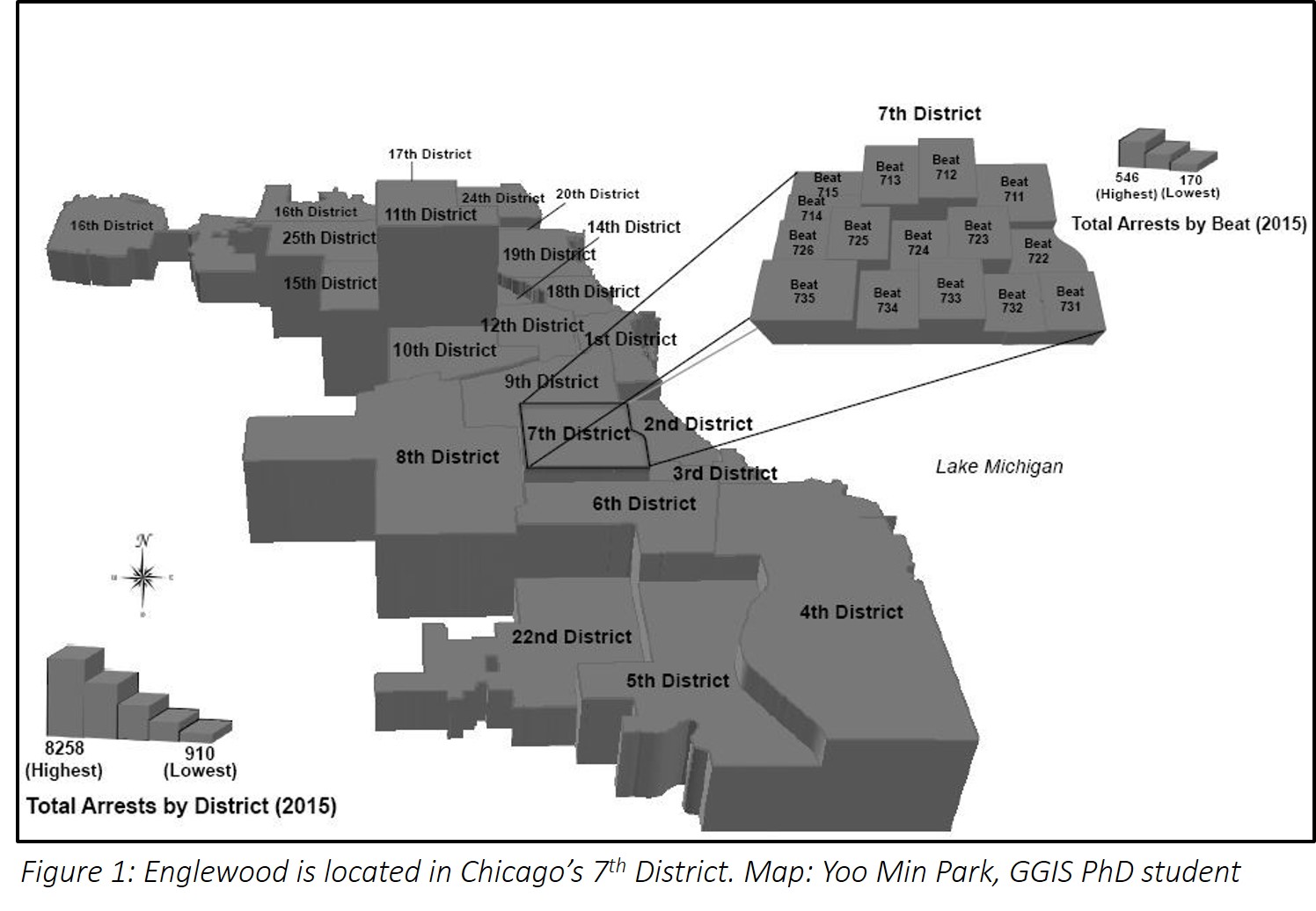

GEOG 484 – Cities, Crime, and Space. Dr. Jefferson researches urban policing to explore how the criminal justice system affects people and neighborhoods in US cities, with a focus on New York City and Chicago. He spent the summer of 2015 in Englewood, a neighborhood on Chicago’s south side, researching how police and residents were using geographic information systems to map and reduce crime (See Figure 1).

We asked Dr. Jefferson to reflect on the problems facing Chicago communities such as Englewood, and to explore possible solutions from a geographic perspective.

What is the biggest challenge facing the Chicago Police Department?

What’s happening with the Chicago Police Department is so complex it can be difficult to think about a starting point to turn things around. As a human geographer, I am inclined to look at the policing crisis from the standpoint of the spatial relations that foster conflict. From this perspective, two major obstacles to substantive police reform in Chicago come to mind.

The first and most difficult issue to deal with is the concentrated and trenchant poverty in parts of the west and south sides. There are several pockets of the city where schools have been shut down, and jobs offering livable wages have all but disappeared. The scenario is a recipe for illicit drug markets, and the gang violence that often accompany them. I think this can encourage an us-versus-them mentality for officers working beats in these areas, which fans the flames of antagonism. Second, Chicago’s city government is considerably decentralized and fractured, which complicates issues of accountability. A centralized and independent review board with subpoena power might overcome some of these structural obstacles. It seems to me only after these issues are resolved that we can turn to police reforms such as mandatory body cameras or non-lethal weapons. Each reform would definitely help, but only so much without substantive changes to the deeper political economic realities spurring crime and police violence.

How can communities, cities, and states make their police forces more accountable?

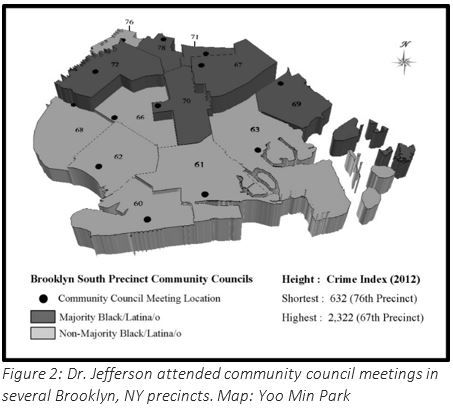

The research I did in New York (Fig. 2) yielded two basic insights that I think Chicago activists might find useful. First, in New York, there was a concerted effort to mention the many different social groups who found themselves subjects of discriminatory policing. In addition to communities of color, Communities united for Police Reform made sure to emphasize that the LGBTQ community, homeless people, the drug addicted, and sex workers also found themselves targets of selective policing. I really believe this commitment to giving voice to a variety of social groups helped build a critical mass that forced the hands of candidates in the 2014 mayoral election. </br>

Second, in researching police accountability activists, I noticed that they seldom connected dots between policing tactics and the economy. In the New York case, “quality of life” and “zero tolerance” approaches to cracking down on homeless and indigent people in the 1990s was directly tied to urban redevelopment. The NYPD was in many ways deployed to remove “undesirable” populations from the city’s main shopping, tourist, and gentrifying areas. While I feel this economic dimension could be stressed a bit more in current critiques of police violence, it seems that activists in Chicago demonstrated great awareness of this connection during the Black Friday (November 27th, 2015) protests.

Further reading:

Jefferson, B.J. 2014. “Neoliberalizing Anticrime Activism: Civilian Patrols & the Post-welfarist Citizen,” Spaces & Flows, 4(3): 59-74

Jefferson, B.J. 2015. “Zero Tolerance for Zero Tolerance?: How Zero Tolerance Discourse Mediates Police Reform Activism,” City, Culture, & Society, 6: 9-17.